India’s educational system underwent significant transformations during British rule, laying the foundation for modern education in the country. The British colonial administration introduced a structured system of education that emphasized English language instruction, modern sciences, and humanities. This period saw the establishment of universities, colleges, and schools that followed a Western-style curriculum, fundamentally altering the traditional methods of learning prevalent in India. Despite its colonial motivations, the educational reforms initiated during this era contributed to the intellectual and professional development of Indian society, fostering a new class of educated individuals who played crucial roles in the socio-political landscape of modern India.

Before the advent of the East India Company, Sanskrit and Persian schools were flourishing in India. They were attached to Temples and mosques, respectively. Pupils were taught Theology. Logic, Law, Philosophy, etc. They were managed with the help of endowments made by the native rulers. The Company authorities followed a policy of non-interference with the native education and culture. Warren Hastings established a madrasa (School) at Calcutta for educating the Muslim children of high families.

The Charter Act of 1813 provided for the allotment of a lakh of rupees every year, for imparting scientific knowledge to the inhabitants of the British dominion. Raja Ram Mohan Roy realised ‘the need for Western education for Indians and agitated for it. He opposed the idea of establishing a Sanskrit College at Calcutta. The spread of Christianity and the teaching of Western culture were taken up simultaneously by the missionaries. In 1818, the Bishop College was founded at Calcutta with the dual purpose of training Christian preachers and teaching English to Hindus and Muslims In 1834, the Elphinstone College was founded in Bombay with the aim of training a class of people for higher employment in the civil administration of India.

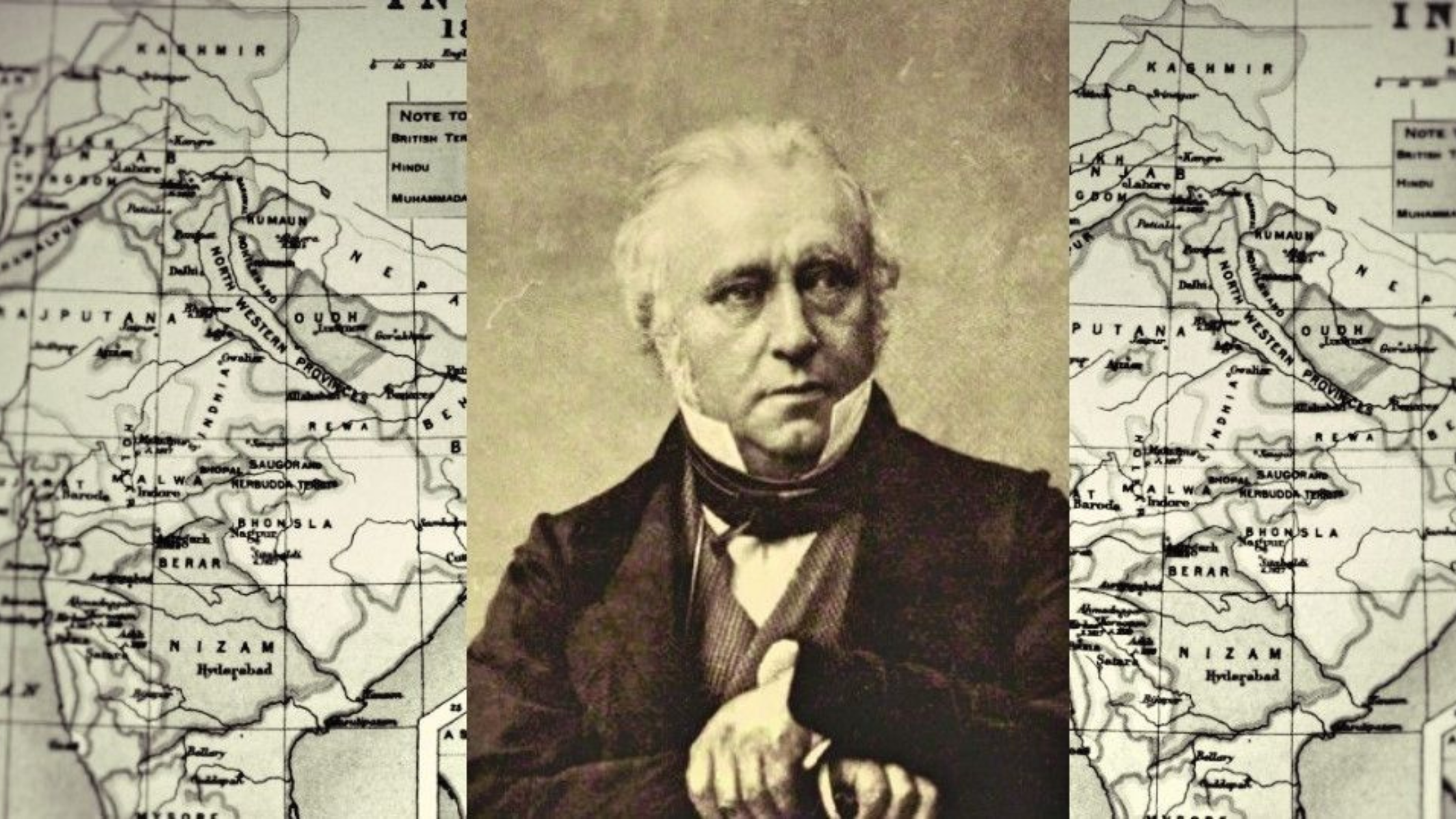

Bentinck’s decision, 1835:

Lord Macaulay, as Chairman of the Education Committee, recommended the introduction of teaching English and Western sciences in Indian schools. Accordingly, Lord Bentinck resolved that the aim of the Government should be to promote English literature and Western sciences in India. All the money sanctioned by the state should be spent on English education only. It should not be spent on Oriental education at all. The Oriental schools would not be abolished but they would not get state aid. Against this decision, 8000 Muslims of Calcutta protested and submitted a petition stating that English education would lead to conversions to Christianity. But their appeal was turned down.

Establishment of Universities, 1857:

Sir Charles Wood prepared a detailed plan for developing education in India. His recommendations of 1854 are described as the Magna Carta of English education in India. They include the following proposals:

a) Universities should be established in Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta on the model of the London University. Each university should have a Chancellor, a Vice-Chancellor, and a Senate. Professorships in different subjects like law, civil engineering, and Oriental languages were to be established.

b) Both English and Indian languages were to be the media for teaching Western sciences.

c) More institutions for training teachers for all classes were to be started.

d) More attention was to be paid to the spread of elementary education.

e) A Director of Public Instruction was to be appointed in every province. Female education was to be given more encouragement.

The Wood’s despatch was submitted to the Directors during the time of Lord Dalhousie.

The Hunter Commission of 1882:

Lord Ripon appointed the Hunter Commission to study the implementation of Wood’s despatch and make further recommendations. The Commission suggested the gradual withdrawal of the State from the direct management of educational institutions. Ordinary and special grants were to be made to the colleges. The head of the institution or a lecturer should address the assembly of students on the duties of man frequently. Elementary schools should be supervised by Inspectors appointed by the Government. The Commission recommended that all the secondary schools should be handed over to private management as far as possible. The government accepted the report and higher education progressed rapidly during the next few decades.

Educational changes under Lord Curzon, 1904:

Lord Curzon appointed the Raleigh Commission to enquire into the condition and progress of the universities established in British India. On the basis of its report, Curzon introduced the Universities Act of 1904. According to it, the governing bodies of the universities were reorganised. A University Senate was to have 50 to 100 members, but of them, the elected members were to be only 20 for the Universities of Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras. Rules and regulations for affiliation of colleges to the universities were clearly laid down and they were to be rigorously followed. The government was given certain powers over the working of the Senates. The Viceroy was to define the territorial limits of the universities.

Curzon became unpopular by passing this Act. The Act tightened the grip of the government on the universities. The proportion of nominated members in the Senates was very much increased. The Director of Public Instruction was made an ex-officio member of the Senate. The main result of this Act was the Europeanisation of the Senates and Syndicates. In 1913 Lord Hardinge realised the need for additional teaching and residential universities. He resolved to start teaching universities at Dacca, Aligarh, and Benares. Affiliating universities were to be started at Rangoon, Patna, and Nagpur. Owing to the outbreak of the First World War, the resolution was not implemented immediately. But universities were started at Benares and Patna in 1916 and 1917 respectively.

Calcutta University Commission of 1919:

Lord Chelmsford appointed the Sadler Commission to make a comprehensive inquiry into the problems of Calcutta University. The Commission made the following recommendations:

a) The intermediate classes of the university were to be transferred to the secondary schools.

Secondary and Intermediate education should be controlled by a Board of Secondary Education but not by the University.

b) The duration of the Degree course should be three years instead of two.

c) The vernacular language should be the medium of instruction in the high school classes.

d) The universities should be managed by the provincial governments instead of the central government.

However the recommendations of the Commission were not fully implemented. Universities were established at Dacca and Lucknow in 1920, at Allahabad in 1921, and at Delhi in 1922. In 1919, under the Dyarchy, the Department of Education was made a transferred subject and was entrusted to the Indian ministers. In 1935, the entire university education was put under the control of the provincial governments.

Other important developments:

a) The Indian Women’s University was started at Poona in 1916 by Prof. D. K. Karve and it was transferred to Bombay in 1936.

b) In 1921, Rabindranath Tagore founded the Viswabharathi University at Santiniketan. It is famous for its universal outlook and the happy blending of Western and Eastern cultures.

c) In 1925, an Inter-University board was constituted to coordinate the workings of the universities.

d) Compulsory and free primary education were introduced in many provinces in 1935.

In spite of all such efforts, the percentage of literacy was only 12 by 1941.

The educational reforms introduced during British rule in India left a lasting impact on the country’s academic and intellectual framework. While these changes were initially driven by colonial interests, they inadvertently facilitated the rise of an educated middle class that would eventually spearhead the movement for independence. The introduction of Western-style education, with its focus on critical thinking and scientific inquiry, played a pivotal role in modernizing Indian society. The legacy of British educational policies continues to influence India’s education system today, underscoring the complex interplay between colonial history and contemporary development. Despite the challenges and criticisms, the period of British rule undeniably set the stage for the advancement of education in India, contributing to its emergence as a knowledge-driven nation in the post-independence era.