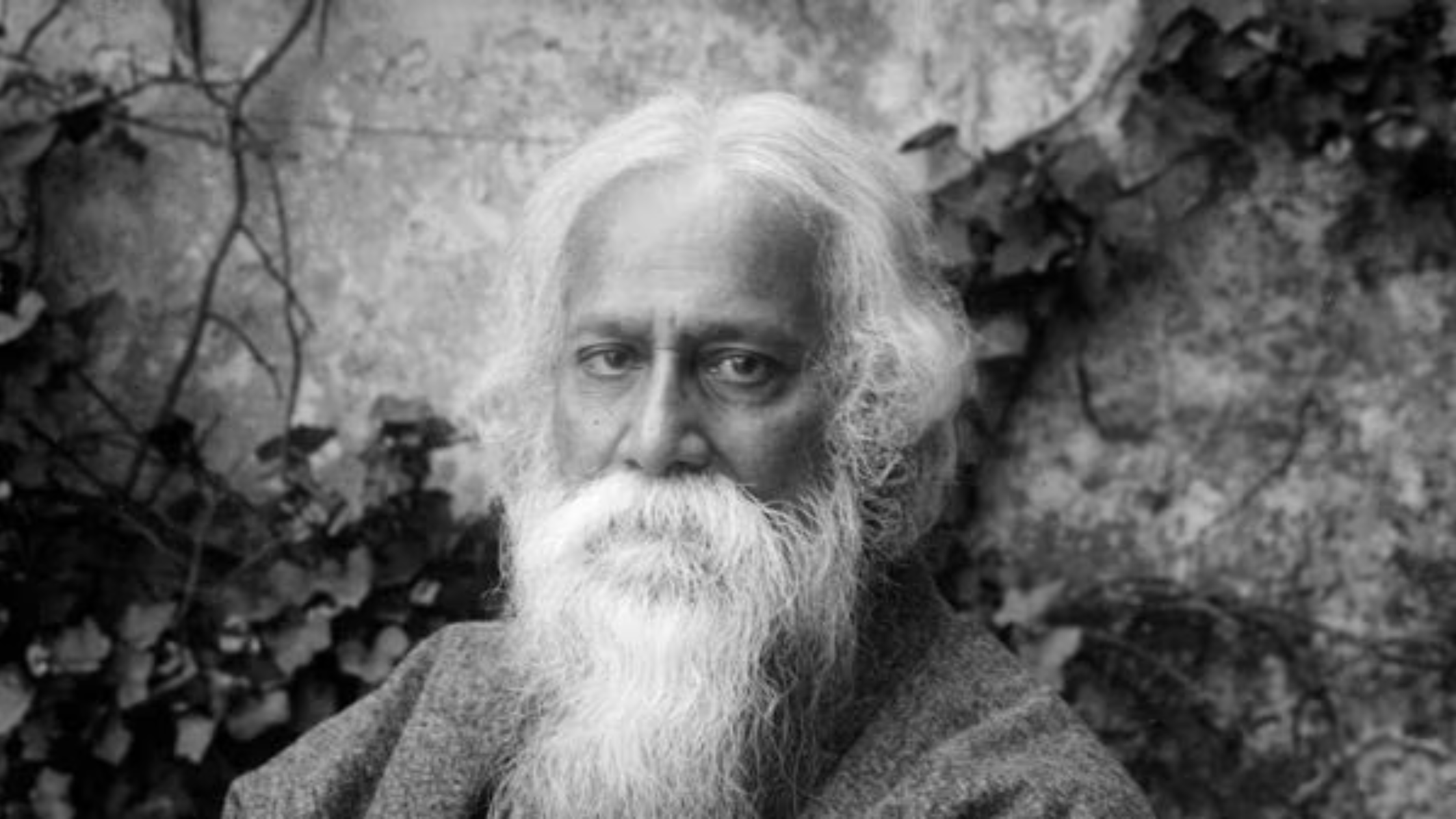

Rabindranath Tagore, a highly influential and exceptionally talented polymath in literature, had a tremendous impact on both Indian culture and the global community. Tagore, born in 1861 in Calcutta, was a polymath who excelled in various fields like poetry, playwriting, book writing, philosophy, and education. His work went beyond national boundaries and encompassed universal issues. In 1913, he became the first person from outside of Europe to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which acknowledged his poetic and profoundly humanistic collection of writings. Tagore’s writings exhibit spiritual profundity, profound humanism, and captivating imagery, demonstrating his dedication to social reform, innovative education, and the integration of Eastern and Western philosophical traditions. His contributions transcend literature and encompass music, art, as well as the wider cultural and political context of his age, establishing him as a pivotal figure in India’s Renaissance and a worldwide representative of Indian thinking and culture.

Rabindranath Tagore, the first non-European to be awarded a Nobel Prize, navigated the intricacies of the political landscape during his era with remarkable complexity. Born in 1861, just after the 1857 Mutiny (also known as the First War of Indian Independence), he came from an affluent Bengali family of high social status. From the beginning, he was immersed in the vibrant cultural and political atmosphere of late colonial rule in India. The extensive variety and adaptability of his literary works, including novels, poetry, plays, songs, and paintings, can be attributed to the liveliness of the era in which he lived. These works served as tools for him to express his viewpoints on the tumultuous changes that occurred in India starting in the late nineteenth century.

A significant portion of Tagore’s literary works explores the challenges associated with one’s sense of national identity. Gora (Fair Skinned, 1910), written during the early stages of anti-colonialism, explores these themes by focusing on its British protagonist, Gora. Gora, an orphan, is brought up in a Hindu family but later uncovers his actual nature as an adult. Although nationalism was a recurring topic that Tagore addressed throughout his life, his level of participation in the nationalist movement in India varied due to his ideological disagreements with its leaders. Tagore’s patriotism was undeniable, but his concept of “freedom” extended beyond mere political liberation from the British. He was cautious of violent public movements, demonstrating a clear comprehension of the marginalized lesser factions inside the colonial state. Among these, Tagore expressed strong criticism towards two specific movements: the Swadeshi Movement and the emergence of revolutionary nationalism.

The Swadeshi Movement, which commenced with the partition of Bengal in 1905 and persisted until 1908, aimed to undermine the economic dominance of the British in India. In response to the monopolistic control over production that allowed the British to sell goods to Indians at excessively high prices, a significant number of people in Bengal made the decision to boycott foreign goods and instead support domestically produced ones. This movement, known as swadeshi (meaning “of one’s own country”), aimed to promote self-sufficiency. Although initially appearing as a successful method of opposition, the campaign neglected to consider the substantial financial setbacks experienced by small merchants, especially those belonging to the Muslim community. Tagore’s novel, Ghare Baire (The Home and the World, 1916), portrays the plight of Muslim shopkeepers who are coerced by the public to burn their British goods in a highly dramatic and ritualistic fashion. In the novel, Nikhil, who is a zamindar or landlord known for his good intentions, is seen as a representative of Tagore’s views. When he speaks out against the mistreatment of the traders residing on his property, he is criticized as being nationalistic and resistant to progress.

The boycott of foreign commodities constituted a minor aspect of a more disconcerting shift in anti-colonial politics, namely the emergence of revolutionary nationalism. Tagore disengaged from the vanguard of the nationalist movement following an incident where an eighteen-year-old named Khudiram Bose unintentionally caused the death of a lady and child while attempting to assassinate the magistrate of Muzzafarpur, a town in the Indian state of Bihar. The Home and the World portrays Nikhil’s opposite, Sandip, as a representation of his intense aversion to violence and the accompanying insanity. Sandip had a deceptive charm and an exceptional ability to inspire and captivate others, including Bimala, Nikhil’s wife. During his periods of solitude, his true nature is exposed as narcissistic, malevolent, and self-centered. Tagore strongly disapproves of Sandip’s association with Bimala.

Nikhil, a progressive individual, desires a marriage with Bimala that is based on equality and companionship. He encourages her to read and he introduces her to his friends. However, Bimala becomes captivated by Sandip, who quickly engulfs her in the thrill and exhilaration of his presence. Sandip goes as far as to name her Mother India and idolize her as a Hindu deity, which later becomes a symbol of Indian liberation in the novel. On one hand, the utilization of Hindu symbols in a political context during a national fight brings a sectarian aspect into the Nationalist movement. However, the depiction of the Mother figure also gives rise to fresh problems in the novel. The vocabulary employed by Sandip is concerning due to its overtly sexual nature. Bimala remains oblivious to this fact – rather than empowering her, the power that Sandip bestows upon her merely reduces her to a mere object of sexual desire, a mere representation devoid of any substance. She becomes aware of this fact only after she discovers other connections to focus her attention on, particularly with the young rebel Amulya, towards whom she develops mother emotions. However, by the time she realizes this, it is too late, as the narrative concludes with Nikhil, who is disenchanted and struggling to survive. Tagore persistently criticized revolutionary nationalism and its dependence on spectacle, violence, and sloganeering. His final novel, Char Adhyay (Four Chapters, 1934), further portrays the detrimental consequences of this ideology.

At the conclusion of the narrative, Bimala comes to the realisation that Nikhil possesses a more sophisticated and subtle understanding of the current situation. Nikhil’s narrative voice is characterised by selflessness rather than selfishness. He comprehends that anti-colonialism should not simply involve the outright rejection of all things British, but rather, it should strive to amalgamate the positive aspects of Western society with those of the East. He contends, similar to Tagore’s approach in his speeches and lectures, particularly in his compilation, Nationalism (1917), that “freedom” encompasses more than only political liberation from the British. Instead, it refers to the capacity to be sincere and genuine with oneself, as without this, self-governance becomes devoid of significance. These beliefs, naturally, eventually formed the fundamental principles of the thought of another nationalist hero, Mahatma Gandhi.

The enduring impact of Rabindranath Tagore as a prodigious literary figure and cultural pioneer reverberates across. His significant contributions to literature, education, and social reform have had a lasting impact on global culture. Tagore endeavored to dismantle boundaries and cultivate a more profound comprehension among many cultures through his poetry, prose, and educational initiatives. His work serves as evidence of the influence of art and intelligence in addressing the shared human experience and advocating for a more balanced world. As we contemplate Tagore’s life and accomplishments, we are reminded of the lasting significance of his principles in the contemporary world, where the pursuit of peace, comprehension, and societal equity remains as pressing as ever. Tagore’s conception of a global community bound together by ingenuity, compassion, and collective human nature remains a source of motivation and direction for forthcoming cohorts.